In this section we’re going to create some real files to work with. To avoid accidentally trampling over any of your real files, we’re going to start by creating a new directory, well away from your home folder, which will serve as a safer environment in which to experiment:

mkdir /tmp/tutorial

cd /tmp/tutorial

Notice the use of an absolute path, to make sure that we create the tutorial directory inside /tmp. Without the forward slash at the start the mkdir command would try to find a tmp directory inside the current working directory, then try to create a tutorial directory inside that. If it couldn’t find a tmp directory the command would fail.

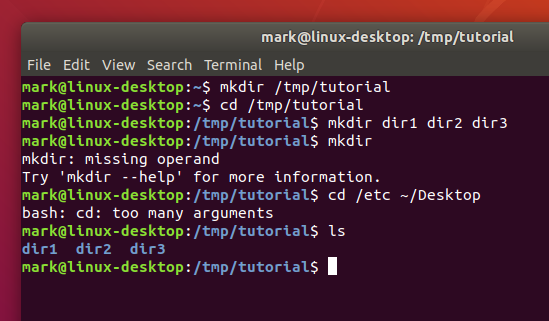

In case you hadn’t guessed, mkdir is short for ‘make directory’. Now that we’re safely inside our test area (double check with pwd if you’re not certain), let’s create a few subdirectories:

mkdir dir1 dir2 dir3

There’s something a little different about that command. So far we’ve only seen commands that work on their own (cd, pwd) or that have a single item afterwards (cd /, cd ~/Desktop). But this time we’ve added three things after the mkdir command. Those things are referred to as parameters or arguments, and different commands can accept different numbers of arguments. The mkdir command expects at least one argument, whereas the cd command can work with zero or one, but no more. See what happens when you try to pass the wrong number of parameters to a command:

mkdir

cd /etc ~/Desktop

Back to our new directories. The command above will have created three new subdirectories inside our folder. Let’s take a look at them with the ls (list) command:

ls

If you’ve followed the last few commands, your terminal should be looking something like this:

Notice that mkdir created all the folders in one directory. It didn’t create dir3 inside dir2 inside dir1, or any other nested structure. But sometimes it’s handy to be able to do exactly that, and mkdir does have a way:

mkdir -p dir4/dir5/dir6

ls

This time you’ll see that only dir4 has been added to the list, because dir5 is inside it, and dir6 is inside that. Later we’ll install a useful tool to visualise the structure, but you’ve already got enough knowledge to confirm it:

cd dir4

ls

cd dir5

ls

cd ../..

The “-p” that we used is called an option or a switch (in this case it means “create the parent directories, too”). Options are used to modify the way in which a command operates, allowing a single command to behave in a variety of different ways. Unfortunately, due to quirks of history and human nature, options can take different forms in different commands. You’ll often see them as single characters preceded by a hyphen (as in this case), or as longer words preceded by two hyphens. The single character form allows for multiple options to be combined, though not all commands will accept that. And to confuse matters further, some commands don’t clearly identify their options at all, whether or not something is an option is dictated purely by the order of the arguments! You don’t need to worry about all the possibilities, just know that options exist and they can take several different forms. For example the following all mean exactly the same thing:

# Don't type these in, they're just here for demonstrative purposes

mkdir --parents --verbose dir4/dir5

mkdir -p --verbose dir4/dir5

mkdir -p -v dir4/dir5

mkdir -pv dir4/dir5

Now we know how to create multiple directories just by passing them as separare arguments to the mkdir command. But suppose we want to create a directory with a space in the name? Let’s give it a go:

mkdir another folder

ls

You probably didn’t even need to type that one in to guess what would happen: two new folders, one called another and the other called folder. If you want to work with spaces in directory or file names, you need to escape them. Don’t worry, nobody’s breaking out of prison; escaping is a computing term that refers to using special codes to tell the computer to treat particular characters differently to normal. Enter the following commands to try out different ways to create folders with spaces in the name:

mkdir "folder 1"

mkdir 'folder 2'

mkdir folder\ 3

mkdir "folder 4" "folder 5"

mkdir -p "folder 6"/"folder 7"

ls

Although the command line can be used to work with files and folders with spaces in their names, the need to escape them with quote marks or backslashes makes things a little more difficult. You can often tell a person who uses the command line a lot just from their file names: they’ll tend to stick to letters and numbers, and use underscores (“_”) or hyphens (“-”) instead of spaces.

Our demonstration folder is starting to look rather full of directories, but is somewhat lacking in files. Let’s remedy that by redirecting the output from a command so that, instead of being printed to the screen, it ends up in a new file. First, remind yourself what the ls command is currently showing:

ls

Suppose we wanted to capture the output of that command as a text file that we can look at or manipulate further. All we need to do is to add the greater-than character (“>”) to the end of our command line, followed by the name of the file to write to:

ls > output.txt

This time there’s nothing printed to the screen, because the output is being redirected to our file instead. If you just run ls on its own you should see that the output.txt file has been created. We can use the cat command to look at its content:

cat output.txt

Okay, so it’s not exactly what was displayed on the screen previously, but it contains all the same data, and it’s in a more useful format for further processing. Let’s look at another command, echo:

echo "This is a test"

Yes, echo just prints its arguments back out again (hence the name). But combine it with a redirect, and you’ve got a way to easily create small test files:

echo "This is a test" > test_1.txt

echo "This is a second test" > test_2.txt

echo "This is a third test" > test_3.txt

ls

You should cat each of these files to check their contents. But cat is more than just a file viewer - its name comes from ‘concatenate’, meaning “to link together”. If you pass more than one filename to cat it will output each of them, one after the other, as a single block of text:

cat test_1.txt test_2.txt test_3.txt

Where you want to pass multiple file names to a single command, there are some useful shortcuts that can save you a lot of typing if the files have similar names. A question mark (“?”) can be used to indicate “any single character” within the file name. An asterisk (“*”) can be used to indicate “zero or more characters”. These are sometimes referred to as “wildcard” characters. A couple of examples might help, the following commands all do the same thing:

cat test_1.txt test_2.txt test_3.txt

cat test_?.txt

cat test_*

More escaping required

As you might have guessed, this capability also means that you need to escape file names with ? or * characters in them, too. It’s usually better to avoid any punctuation in file names if you want to manipulate them from the command line.

If you look at the output of ls you’ll notice that the only files or folders that start with “t” are the three test files we’ve just created, so you could even simplify that last command even further to cat t*, meaning “concatenate all the files whose names start with a t and are followed by zero or more other characters”. Let’s use this capability to join all our files together into a single new file, then view it:

cat t* > combined.txt

cat combined.txt

What do you think will happen if we run those two commands a second time? Will the computer complain, because the file already exists? Will it append the text to the file, so it contains two copies? Or will it replace it entirely? Give it a try to see what happens, but to avoid typing the commands again you can use the Up Arrow and Down Arrow keys to move back and forth through the history of commands you’ve used. Press the Up Arrow a couple of times to get to the first cat and press Enter to run it, then do the same again to get to the second.

As you can see, the file looks the same. That’s not because it’s been left untouched, but because the shell clears out all the content of the file before it writes the output of your cat command into it. Because of this, you should be extra careful when using redirection to make sure that you don’t accidentally overwrite a file you need. If you do want to append to, rather than replace, the content of the files, double up on the greater-than character:

cat t* >> combined.txt

echo "I've appended a line!" >> combined.txt

cat combined.txt

Repeat the first cat a few more times, using the Up Arrow for convenience, and perhaps add a few more arbitrary echo commands, until your text document is so large that it won’t all fit in the terminal at once when you use cat to display it. In order to see the whole file we now need to use a different program, called a pager (because it displays your file one “page” at a time). The standard pager of old was called more, because it puts a line of text at the bottom of each page that says “–More–” to indicate that you haven’t read everything yet. These days there’s a far better pager that you should use instead: because it replaces more, the programmers decided to call it less.

less combined.txt

When viewing a file through less you can use the Up Arrow, Down Arrow, Page Up, Page Down, Home and End keys to move through your file. Give them a try to see the difference between them. When you’ve finished viewing your file, press q to quit less and return to the command line.

Unix systems are case-sensitive, that is, they consider “A.txt” and “a.txt” to be two different files. If you were to run the following lines you would end up with three files:

echo "Lower case" > a.txt

echo "Upper case" > A.TXT

echo "Mixed case" > A.txt

Generally you should try to avoid creating files and folders whose name only varies by case. Not only will it help to avoid confusion, but it will also prevent problems when working with different operating systems. Windows, for example, is case-insensitive, so it would treat all three of the file names above as being a single file, potentially causing data loss or other problems.

You might be tempted to just hit the Caps Lock key and use upper case for all your file names. But the vast majority of shell commands are lower case, so you would end up frequently having to turn it on and off as you type. Most seasoned command line users tend to stick primarily to lower case names for their files and directories so that they rarely have to worry about file name clashes, or which case to use for each letter in the name.

Good naming practice

When you consider both case sensitivity and escaping, a good rule of thumb is to keep your file names all lower case, with only letters, numbers, underscores and hyphens. For files there’s usually also a dot and a few characters on the end to indicate the type of file it is (referred to as the “file extension”). This guideline may seem restrictive, but if you end up using the command line with any frequency you’ll be glad you stuck to this pattern.